What is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)?

Many therapists utilize theories of psychotherapy to inform their therapy practice. These “theoretical orientations” serve as a framework for therapy. They help therapists conceptualize the common struggles clients face and give us tools and interventions to help our clients make progress towards their goals. The primary theoretical orientation that I utilize in my practice is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, otherwise known as ACT (pronounced like the word “act,” not the acronym “A-C-T”).

About Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy was founded in the 1980s by clinical psychologist Steven Hayes. According to the Association for Contextual Behavioral Science, ACT is a research-based psychological intervention that combines mindfulness and acceptance practices with behavior change strategies to help clients work towards their therapeutic goals. One of the main goals of ACT is to help clients work towards “psychological flexibility,” which means grounding yourself in the present moment and conscientiously acting in accordance with your values.* To use my own words, ACT is simply about more closely observing your internal mental landscape, changing your relationship with your thoughts so that you can approach them with less judgment, and altering your behaviors so that they’re more in line with what’s really important to you.

*Hayes, S. ACT. Association for Contextual Behavioral Science.

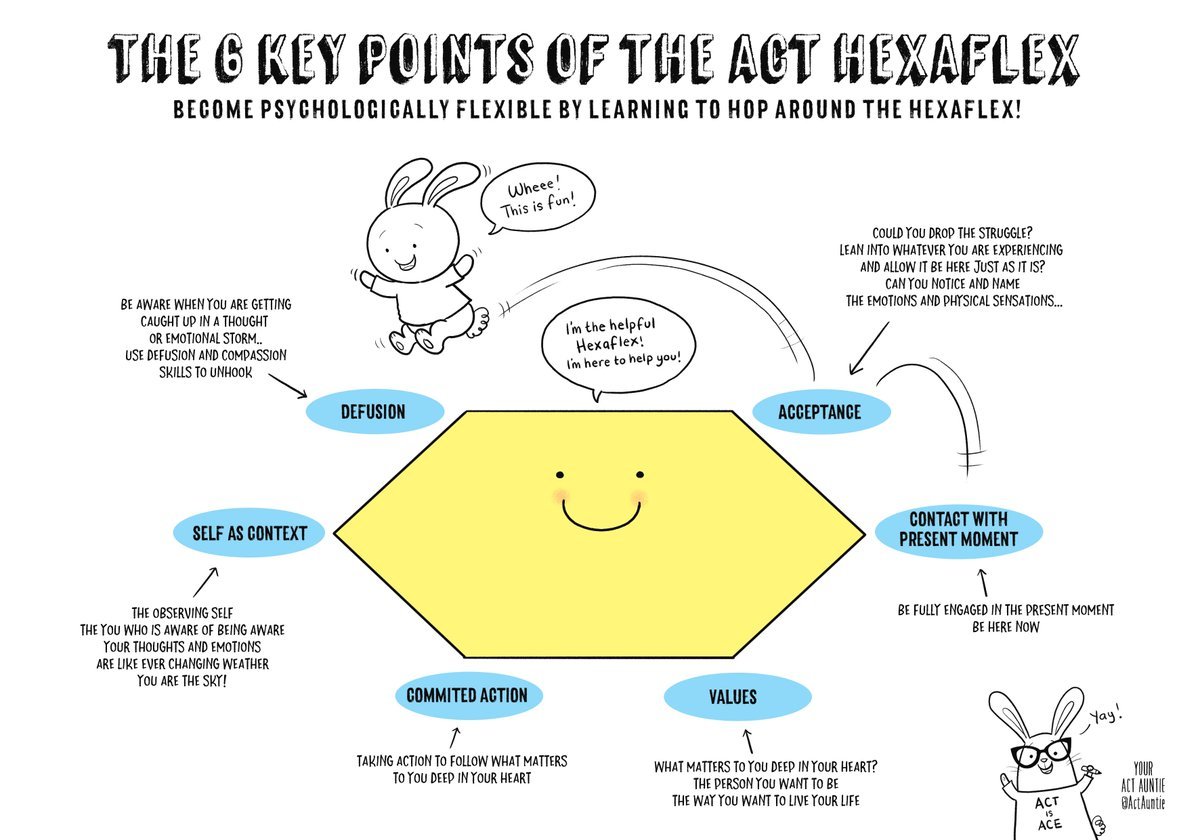

There’s a somewhat-confusing-at-first-but-ultimately-pretty-cool diagram explaining the six major components of psychological flexibility called the “ACT Hexaflex.” Take a peek below for a quick description of these six tenets of ACT. Through the consistent use of these skills, the idea is that you can become more psychologically flexible and better manage anxiety, stress, depression, self-doubt, and avoidant behaviors, among many other common mental health concerns.

The ACT Hexaflex. Credit to Your ACT Auntie for this awesome diagram!

ACT in Practice: An Example

Let’s take an example. Say you’re really wanting to start dating, but you notice yourself getting stuck. You download a dating application, but when you open it and start creating your profile, you get in your head. You start doubting yourself about whether you’re really going to find anyone who likes you, whether you’re attractive enough, successful enough, or charming enough. What am I even going to message someone if we match?? And all this noise in your mind turns into avoidance. You stop opening the app. You find it overwhelming to read any messages or look to see if you’ve gotten any matches. So you end up throwing up your hands and tell yourself “maybe next month.” That leads to you feeling more depressed - you want a partner so badly, and building a family is one of your most important goals in life.

If we were to view what’s happening in this example through an ACT lens, what’s happening is you’re getting “fused” with all these overwhelming thoughts. Dating is something that’s really important to you, and your negative thoughts are getting in your way towards working towards that goal. So by engaging in self-as-context, you can become more aware that these negative thoughts are just thoughts. You can use the skill of cognitive defusion to remind yourself that these thoughts aren’t really helping you move towards finding a partner. They’re anxious thoughts your brain is spitting out at you. There’s really no use to be gained by listening to those thoughts and buying into them - they will only make you feel worse about yourself. What really matters is going on a date, because you value finding a partner. Next time you open the dating app, you engage in some present moment awareness. What are your thoughts and feelings? You’re starting to feel anxious - you’re feeling it in your body, you’re noticing some self-doubt creeping in. Now we can use some acceptance. OK, so we’re feeling anxious. We have a choice now - do we avoid the next step in dating? Or do we “act” despite feeling anxious, alongside our anxiety, towards committed action? Do we give into the anxiety or schedule that date? By practicing these six components of psychological flexibility, you can move past inflexibility, struggle, and avoidance, and take control of your life.

This is just a brief overview of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. For more information, visit the Association for Contextual Behavioral Science website or watch this introductory video on Youtube.